The Bible is a compilation of works authored by various authors rather than a single work. This begs the question of why some writings are regarded as canonical and others as canonical outside of the Bible. Who then made this choice?

Some key terms

Before delving into this subject, it is important to clarify a few phrases that Christians and academics use often:

- Canon: When referring to the Bible, the term “canon” designates the group of works that are recognized as authoritative.

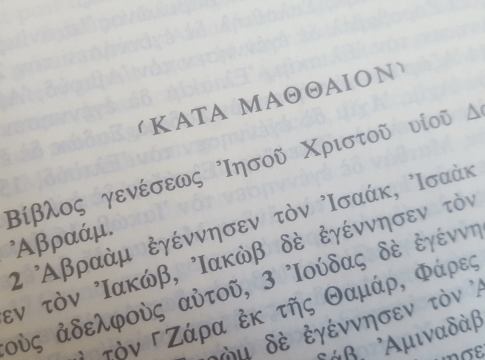

- The books of the Bible that were composed prior to the birth of Jesus Christ are known as the Old Testament, Hebrew Bible, or Jewish Scriptures. They are acknowledged by both Christians and Jews as the infallible Word of God. They had [Hebrew writing].

- The books of the Bible that were written after the birth of Jesus Christ are known as the New Testament. They are not recognized as God’s Word by Jews. Believers do.

- The works published before the birth of Jesus Christ are known as Deuterocanonical literature or apocrypha. They are not included in the Jewish Scriptures and were primarily written in Greek, not Hebrew.

How it all started

It took several centuries for the Old Testament writings to be written, making the establishment of a canonical order impractical. But individual books held influence even before the canon was finished. For example, the Ten Commandments that Moses was given by God were supremely authoritative from the start. In addition, the book of Deuteronomy was composed as a set covenant document that was unchangeable. It should be read aloud on a regular basis (Deuteronomy 31:9–13), be maintained in the holy tent (Exodus 25:16–25:21; Deuteronomy 10:1–5; Deuteronomy 31:24–26), and be owned by the monarch (Deuteronomy 17:18).

Following several years, King Josiah acknowledged these scriptures as final (see to 2 Kings 22–23 and 2 Chronicles 34). Nehemiah 8 tells a similar tale, in which “the Book of the Law of Moses that the Lord had commanded Israel” is read aloud to the entire populace, closely examined, and complied with. And the later writings of the Old Testament make frequent allusions to the earlier ones. Therefore, these Bible texts were revered even though there was no established canon at the time.

The canon of the Old Testament

It is challenging for historians to pinpoint the exact moment the canon was closed and the period after which there was widespread consensus over which Bible books did and did not belong to it because the various books were written and transferred on distinct scrolls for a considerable amount of time. The precise number and arrangement of these books didn’t become more significant or traceable until much later, when the Scriptures were recorded in books rather than on individual scrolls.

Numerous historical accounts suggest that there was a definite canon, comprising all the Bible books of the so-called Masoretic text, at the time of Jesus’ birth, or roughly the year 0 AD. Jesus frequently referenced from several of these texts and acknowledged them as authoritative because he was a Jew and was well-versed in the Jewish Scriptures. Other authors of the New Testament Bible followed suit. Therefore, the Hebrew Scriptures that the Jews, including Jesus, acknowledged as the inspired word of God were “copied” by the Christians rather than creating their own canon of Old Testament books.

Deuterocanonical books

The Septuagint, an ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, adds much more complexity. Some books included in this edition were considered authoritative by early Christians even though they are not included in the Jewish Scriptures.[1]

Seven of these publications are now recognized by the Roman Catholic church as canonical, based on the 1546 Council of Trent verdict. The canon of the Ethiopian churches differs slightly from that of the Eastern Orthodox and Armenian churches, which add additional books or portions to their canon.

Protestant churches differ in how they see these writings, although extracanonical is how they are all understood. This indicates that the apocrypha are not regarded as a part of the infallible, inspired word of God. They lack the same authority as the canonical works as a result. The apocrypha is made up of “just” human-written writings that might provide insightful insights but might also have errors.

The canon of the New Testament

Jesus’ own teachings were regarded as final by those who followed Him. By the end of the first century, Christians were using passages from the Old Testament and the words of Jesus as “scripture” (see 1 Timothy 5:18, which quotes Matthew 10:10 and Luke 10:7). Moreover, a few of Jesus’ disciples, like the apostle Paul, saw themselves as credible arbiters of the truth.

Other authors of the Bible acknowledged this assertion and added his letters to the canon of “scriptures” (see, for instance, 2 Peter 3:15–16). The apostles who adhered to Jesus’ own teachings and whose letters were written by them were topics of discussion (because there were also frauds). Read this page to learn more about the factors and justifications that went into choosing which books to add or exclude from the canon.

Even though the four Gospels were widely considered authoritative, along with Acts, most of the Pauline epistles and several of the longer general epistles, the acceptability of some of the other books was debated till the fourth century. In 367 AD, Athanasius the bishop of Alexandria named the 27 books that are currently accepted by Christians, as the authoritative canon of Scripture. However, this was not just his personal opinion. He wrote down the consensus of a larger group of religious authorities. On various church councils, (AD 382 in Rome, AD 393 in Hippo, and AD 397 in Carthage) the list of New Testament books that were recognized as canonical, was officially noted down. Later on, Roman Catholic and Protestant church councils stated their respective decisions on the canon and on the status of the apocrypha.

God led the process

It is important to remember that while mankind discussed and argued about the books that should be included in the canon of Scripture, we think that in the end, God guided the Church in choosing which texts should be considered part of God’s inspired word. No further volumes can be added to the Bible because it was completed (see Revelation 22:18).

[1] See “Was there a Septuagint canon?” for more specific details regarding the current status of these works.